Includes 2 easels, Administration Manual, USB Flash Drive (contains Technical Manual, Scoring Manual, Stimulus Audio Files), Form B Record Forms (25), Form B Response Booklet (25), 3 Form B Written Expression booklets (2 each), labeled tote bag, plus 100 Q-global Score Reports. Add; KTEA-3 Q-global. Score Report. 32450 $ 2.90 (Price per Report). KTEA-II Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement Second Edition Name: JONES, MARISA T. Age: 14:6 Current Grade: 8 Sex: Female Form A Test Date: Examiner: MS. JANICE SMITH Score Summary Table Grade Norms: Fall, Grade 8 Subtest Raw Score Sum of Subtest Standard Scores Standard Score 90% Confidence Interval Percentile Rank Descriptive. . The KTEA–3 Comprehensive Form represents a substantial revision of the KTEA–II including:. Updated norms. Four(4) new subtests. Revised subtests with new items and improved content coverage. Updated artwork. Simplification of administration procedures to enhance the user friendliness of the test. The KTEA-II Brief Form is intended for screening examinees on their global skills in mathematics, reading, and written language. The results of the screening may be used to determine the need for follow-up testing. If test scoring is the responsibility of the test user, provide adequate training.

By Elizabeth O. Lichtenberger Kristina C. BreauxJohn Wiley & Sons

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, LtdAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-470-55169-1

Chapter One

OVERVIEWOver the past few years, there have been many changes affecting those who administer standardized achievement tests. New individually administered tests of achievement have been developed, and older instruments have been revised or renormed. The academic assessment of individuals from preschool to post-high school has increased over the past years due to requirements set forth by states for determining eligibility for services for learning disabilities. Individual achievement tests were once primarily norm-based comparisons with peers but now serve the purpose of analyzing academic strengths and weaknesses via comparisons with conormed (or linked) individual tests of ability. In addition, the focus of academic assessment has been broadened to include not only reading decoding, spelling, and arithmetic but also reading comprehension, arithmetic reasoning, arithmetic computation, listening comprehension, oral expression, and written expression (Smith, 2001).

These changes in the field of individual academic assessment have led professionals to search for resources that would help them remain current on the most recent instruments. Resources covering topics such as how to administer, score, and interpret frequently used tests of achievement and on how to apply these tests' data in clinical situations need to be frequently updated. Thus, in 2001, Douglas K. Smith published a book in the Essentials series titled Essentials of Individual Achievement Assessment, which devoted chapters to four widely used individually administered tests of achievement. Smith's book was the inspiration for writing this book, which focuses on the recent second editions of two of the instruments written about in Essentials of Individual Achievement Assessment: the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test (WIAT) and the Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement (KTEA). Because both of these instruments are widely used achievement tests in school psychology and related fields, the third edition of the WIATand the second edition of the KTEA are deserving of a complete up-to-date book devoted to their administration, scoring, interpretation, and clinical applications. Essentials of WIAT-III and KTEA-II Assessment provides that up-to-date information and includes rich information beyond what is available in the tests' manuals. An entire chapter is devoted to illustrative case reports to exemplify how the results of the WIAT-III and KTEA-II can be integrated with an entire battery of tests to yield a thorough understanding of a student's academic functioning. In a chapter devoted to clinical applications of the tests, the following topics are discussed: the integration of the KTEA-II and WIAT-III with their respective conormed tests of cognitive ability, focusing on the conceptual and theoretical links between tests, and the assessment of special populations, including specific learning disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

PURPOSES AND USES OF ACHIEVEMENT TESTS

The WIAT-III and KTEA-II are used for many reasons including diagnosing achievement, identifying processes, analyzing errors, planning programs, measuring academic progress, evaluating interventions or programs, making placement decisions, and conducting research. Some pertinent applications of these tests are described next.

Diagnosing Achievement

The WIAT-III and KTEA-II provide an analysis of a student's academic strengths and weaknesses in reading, mathematics, written expression, and oral language. In addition, these tests allow for the investigation of related factors that may affect reading achievement, such as Phonological Awareness and Naming Facility (RAN) on the KTEA-II and Early Reading Skills, Oral Word Fluency, Expressive Vocabulary, Receptive Vocabulary, and Oral Discourse Comprehension on the WIAT-III.

Identifying Processes

Pairwise comparisons of subtests on both the WIAT-III and KTEA-II allow examiners to better understand how students take in information (Reading Comprehension versus Listening Comprehension) and express their ideas (Written Expression versus Oral Expression).

Analyzing Errors

The KTEA-II provides a detailed quantitative summary of the types or patterns of errors a student makes on subtests in each of the achievement domains (Reading, Math, Written Language, and Oral Langauge), as well as for Phonological Awareness and Nonsense Word Decoding. Tracking error patterns can help examiners plan appropriate remedial instruction specifically targeting the difficulties a student displays, and the KTEA-II ASSIST software offers instructional strategies to help examiners design appropriate interventions based on a student's error pattern.

The WIAT-III provides skills analysis capabilities that also yield a detailed quantitative summary of the types of errors a student makes. This information helps examiners evaluate a student's error patterns and skill strengths and weaknesses. Each subtest includes sets of items that measure a specific skill or set of skills. The information yielded from analyzing the student's errors through the skills analysis can then be used in the design of an instructional plan or specific intervention for a student.

Planning Programs

The norm-referenced scores, along with the error analysis information, indicate a student's approximate instructional level. These results can help facilitate decisions regarding appropriate educational placement as well as appropriate accommodations or curricular adjustments. The information can also assist in the development of an individualized education program (IEP) based on a student's needs. For young adults, the results can help inform decisions regarding appropriate vocational training or general equivalency diploma (GED) preparation.

Measuring Academic Progress

The two parallel forms of the KTEA-II allow an examiner to measure a student's academic progress while ensuring that changes in performance are not due to the student's familiarity with the battery content. Academic progress can also be measured on the WIAT-III with a retest, taking into consideration any potential practice effect.

Evaluating Interventions or Programs

The WIAT-III and KTEA-II can provide information about the effectiveness of specific academic interventions or programs. For example, one or more of the composite scores could demonstrate the effectiveness of a new reading program within a classroom or examine the relative performance levels between classrooms using different math programs.

Making Placement Decisions

The WIAT-III and KTEA-II can provide normative data to aid in placement decisions regarding new student admissions or transfers from other educational settings.

Conducting Research

The WIAT-III and the KTEA-II Comprehensive Form are reliable, valid measures of academic achievement that are suitable for use in many research designs. Indeed, a brief search of the literature via the PsycINFO database yielded hundreds of articles that utilized the WIAT and the KTEA. The two parallel forms of the KTEA-II make it an ideal instrument for longitudinal studies or research on intervention effectiveness using pre- and post-test designs.

Ktea Ii Scoring Manual 2019

The KTEA-II Brief Form is also a reliable, valid measure of academic achievement that is ideal for research designs that call for a screening measure of achievement. The brevity of the KTEA-II Brief Form makes it useful in estimating the educational achievement of large numbers of prisoners, patients in a hospital, military recruits, applicants to industry training programs, or juvenile delinquents awaiting court hearings, where administering long tests may be impractical.

Screening

The KTEA-II Brief Form is intended for screening examinees on their global skills in mathematics, reading, and written language. The results of the screening may be used to determine the need for follow-up testing.

SELECTING AN ACHIEVEMENT TEST

Selecting the appropriate achievement test to use in a specific situation depends on a number of factors. The test should be reliable, valid, and used only for the purposes for which it was developed. The Code of Fair Testing Practices in Education (Joint Committee on Testing Practices, 2004) outlines the responsibilities of both test developers and test users. Key components of the Code are outlined in Rapid Reference 1.1.

The first factor to consider in selecting an achievement test is the purpose of the testing. Discern whether a comprehensive measure (covering the areas of achievement specified in the Individuals with Disabilities Improvement Act of 2004 [Public Law (PL) 108-446]) is needed or whether a less specific screening measure is appropriate. Another issue is whether an analysis for the identification of a specific learning disability (e.g., ability-achievement discrepancy) will need to be examined. Although PL 108-446 recently removed the requirement of demonstrating an achievement-ability discrepancy from determining eligibility for learning disabilities services, states still have the option to include this discrepancy if they choose. For this purpose, using achievement tests with conormed or linked ability tests is best. To gather diagnostic information and information about the level of skill development, you should use a test with skills analysis procedures.

The second factor to consider in selecting an achievement test is whether a particular test can answer the specific questions asked in the referral concerns. The specificity of the referral questions will help guide the test selection. For example, if the referral concern is about a child's reading fluency, the test you select should have a subtest or subtests that directly assess that domain.

The third factor to consider in selecting an achievement test is how familiar an examiner is with a certain test. Familiarity with a test and experience with scoring and interpreting it is necessary to ethically utilize it in an assessment. If you plan to use a new test in an assessment, you should ensure that you have enough time to get proper training and experience with the instrument before using it.

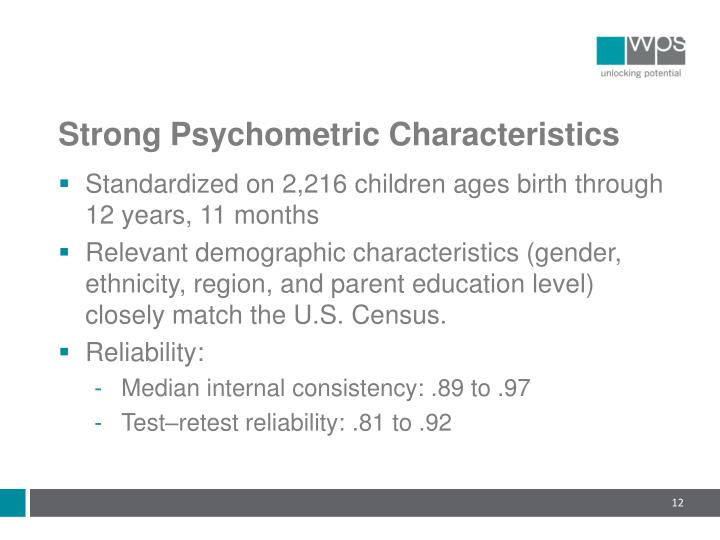

The fourth factor to consider in selecting an achievement test is whether the test's standardization is appropriate. Consider how recent the test's norms are. Most recent major tests of academic achievement are well standardized, but you should still review the manual to evaluate the normative group. See if students with disabilities were included in the standardization sample (which is important when assessing a student suspected of having a learning disability). Also see if appropriate stratification variables were used in the standardization sample.

The fifth factor to consider in selecting an achievement test is the strength of its psychometric properties. Consider whether the test's data have adequately demonstrated its reliability and validity. A test's internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and correlations with other achievement tests and tests of cognitive ability should all be examined. Additionally, consider the floor and ceiling of a test across age levels. Some tests have poor floors at the youngest age levels for the children with the lowest skills, and other tests have poor ceilings at the oldest age levels for the children with the highest skill levels. You can judge the adequacy of the floors and ceilings by examining the standard score range of the subtests and composites for the age range of the student you are assessing.

In Chapter 4 of this book, Ron Dumont and John Willis review what they feel are the strengths and weaknesses of the WIAT-III and KTEA-II, respectively. We encourage examiners to carefully review the test they select to administer, whether it is the WIAT-III, KTEA-II, or another achievement test, to ensure that it can adequately assess the unique concerns of the student for whom the evaluation is being conducted. Rapid Reference 1.2 summarizes the key points to consider in test selection.

ADMINISTERING STANDARDIZED ACHIEVEMENT TESTS

The WIAT-III and KTEA-II are standardized tests, meaning that they measure a student's performance on tasks that are administered and scored under known conditions that remain constant from time to time and person to person. Standardized testing allows examiners to directly compare the performance of one student to the performance of many other students of the same age who were tested in the same way. Strict adherence to the rules allows examiners to know that the scores obtained from the child they tested are comparable to those obtained from the normative group. Violating the rules of standardized administration renders norms of limited value. Being completely familiar with the test, its materials, and the administration procedures allows examiners to conduct a valid assessment in a manner that feels natural, comfortable, and personal-not mechanical. The specific administration procedures for the WIAT-III are discussed in Chapter 2, and those for the KTEA-II are discussed in Chapter 3.

Testing Environment

Achievement testing, like most standardized testing, should take place in a quiet room that is free of distractions. The table and chairs that are used during the assessment should be of appropriate size for the student being assessed. That is, if you are assessing a preschooler, then the table and chairs used should ideally be similar to those that you would find in a preschool classroom. However, if you are assessing an adolescent, adult-size table and chairs are appropriate. For the WIAT-III, the seating arrangement should allow both the examiner and the student to view the front side of the easel. For the KTEA-II, the seating arrangement should allow the examiner to see both sides of the easel. The examiner must also be able to write responses and scores discretely on the record form (out of plain view of the examinee). Many examiners find the best seating arrangement is to be at a right angle from the examinee, but others prefer to sit directly across from the examinee. The test's stimulus easel can be used to shield the record form from the student's view, but if you prefer, you may also use a clipboard to keep the record form out of view. Most importantly, you should sit wherever is most comfortable for you and allows you easy access to all of the components of the assessment instrument.

Establishing Rapport

In order to ensure that the most valid results are yielded from a testing, you need to create the best possible environment for the examinee. Perhaps more important than the previously discussed physical aspects of the testing environment is the relationship between the examiner and the student. In many cases, the examiner will be a virtual stranger to the student being assessed. Thus, the process of establishing rapport is a key component in setting the stage for an optimal assessment.

Ktea Ii Scoring Manual

Rapport can be defined as a relationship of mutual trust or emotional affinity. Such a relationship typically takes time to develop. To foster the development of positive rapport, you need to plan on a few minutes of relaxed time with the student before diving into the assessment procedures. Some individuals are slow to warm up to new acquaintances, whereas others are friendly and comfortable with new people from the get-go. Assume that most students you meet will need time before being able to comfortably relate to you.

Ktea Ii Scoring Manual 2018

You can help a student feel more comfortable through your style of speech and your topics of conversation. Adapt your language (vocabulary and style) to the student's age and ability level (i.e., don't talk to a 4-year-old like you would a teenager, and vice versa). Use a friendly tone of voice, and show genuine personal interest and responsiveness. For shy children, rather than opening up immediately with conversation, try an ice-breaking activity such as drawing a picture or playing with an age-appropriate toy. This quiet interaction with concrete materials may provide an opening to elicit conversation about them.

In most instances, it is best not to have a parent, teacher, or other person present during the assessment, as it can affect the test results in unknown ways. However, when a child is having extreme difficulty separating, it can be useful to permit another adult's presence in the initial rapport-building phase of the assessment to help the child ease into the testing situation. Once the child's anxiety has decreased or once the child has become interested in playing or drawing with you, encourage the student to begin the assessment without the adult present.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Essentials of WIAT-III and KTEA-II Assessment by Elizabeth O. Lichtenberger Kristina C. Breaux Copyright © 2010 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

Part 3 of “What Do These Test Scores Mean?” will focus on understanding academic achievement testing.

Academic achievement tests measure specific academic skills compared to other children at the same grade or age level. They focus on Broad Reading, Writing, Math, and Oral Language skills and also different aspects of the broad areas. Within the Reading domain, there will typically be a task measuring comprehension, a task measuring reading fluency, a task measuring site word recognition, and a task measuring decoding. Math is typically broken down into computations, fluency, and a task measuring mathematical reasoning. Within the Writing domain, there will be a task measuring spelling, writing fluency, and the ability to express oneself through writing. The testing occurs in an individualized setting with a test examiner and the student. The examiner will help the student stay focused and complete the tasks, but will not provide assistance on test items.

Unlike classroom assessments that measure a specific skill that has just been taught, these tests measure basic academic skills. A student’s performance will be compared to other children of the same age. If your child just turned 9, his performance will be compared to others who just turned 9 in the standardized sample. The test measures the level of skills that have been acquired compared to “typical” 9 year olds. Like other standardized tests, achievement tests have also been normed with a standardized sample of children of all ages to develop a range of typical scores. Scores between 90-109 are typically the Average range and consist of the level of skills acquired by most children. 100 is the Mean and the farther away from 100 the score is, the more atypical. In a regular education classroom the majority of students would score in the Average range, Low Average range (80-89), or High Average range (110-119).

Typically, a student’s academic achievement scores will be quite similar to the cognitive ability scores. When the scores are well below measured cognitive potential, it may signify a Learning Disability if other factors are present. However, there are a variety of reasons that cause academic achievement to be discrepant from cognitive abilities.

Some of the most common tests of academic achievement:

-Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Second Edition (WIAT-II)

-Woodcock Johnson, Tests of Achievement, Third Edition (WJ-III)

-Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement, Second Edition (KTEA-II)

See also:

What Do These Scores Mean? – Cognitive Assessments

What Do These Scores Mean? – Behavior Rating Scales